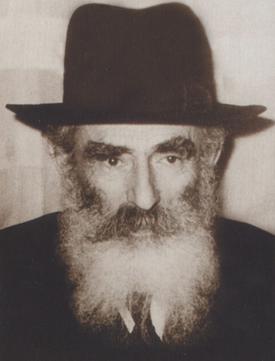

Rav Yechezkel Levenstein zt"l

הרב יחזקאל בן יהודה לוינשטיין זצ"ל

Adar 18 , 5734

Rav Yechezkel Levenstein zt"l

(1884 – 1974) Reb Yechezkel or “Reb Chatzkel” as he was known was the spiritual leader (mashgiach) of two of the most illustrious yeshivas in the world, Mir and Ponovezh. He was grateful for having studied in Kelm where “I merited to grasp that all of man’s life is to awaken and enliven his soul”. In his old age he wrote: I was never attached to matters of this world (olam Hazeh) – and yet what a good (olam Hazeh) world did I enjoy.

After WW I he was invited to become mashgiach of the Lomza yeshiva in Petach Tikva, where he was very happy and successful. However, when the famed mashgiach of Mir, R. Yeruchem Levovitz, passed away in 1936 and he was invited to replace him, Reb Chatzkel assumed that position because he felt obliged to accept in order to retain the character of that illustrious institution.

With the outbreak of WW II in 1939, the Mirrer yeshiva continued to maintain its identity, in large measure due to the indefatigable spirit of Reb Chatzkel. While moving to Kobe, Japan and Shanghai during the war years, the Yeshiva miraculously remained an institution of the highest standard of learning and mussar.

After the war, Reb Chatzkel first came to the United States and began to deliver his lectures and serve as mashgiach in the newly founded Mir yeshiva. However, he soon found that America was totally uncongenial to his spirit, remarking that the materialism was contagious even when one is enclosed in the four amos of the yeshiva. Reb Chatzkel emigrated to Eretz Yisroel in 1949 beginning a fresh career as mashgiach of Mir and then at age 70 he became the mashgiach of Ponovezh.

Perhaps the great power and influence of Reb Chatzkel stemmed from the fact that he never ceased scrutinizing his own behavior, always seeking to improve and take control of his emotions and drives.

He concentrated on strengthening faith, never satisfied with what he had already achieved. The Chazon Ish said that Reb Chatzkel’s faith was palpable. He denigrated the illusory values of contemporary culture. He wrote that though learning Torah was equal to all the mitzvas it was not the purpose of life; the purpose of life is the fear of heaven and the attachment to G-d (deveikus) (Ohr Yechezkel letters, #14). To the degree that a person considers something else of primary importance, to that degree has he made Torah secondary (Letter #364). Seven volumes of his works, Ohr Yechezkel, have been published, including a volume of letters.

Taken from Leaders in the Diaspora

https://breslev.com/259060/

Stories of Rav Yechezkel Levenstein zt"l

The Chazon Ish used to say that there were three giants of mussar who excelled in emuna: In Rav Eliyohu Eliezer Dessler we see his greatness in emuna of mind, in Rav Eliyohu Lopian we see his greatness in emuna of the heart, and in Rav Chatzkel Levenstein we see that he had emuna in his hands – he had experiential emuna, the kind you can touch and feel with your very hands! (Otzros Rabbeinu Yechezkel, p. 23)

One of his talmidim described how during a mussar shmuess in Yeshivas Ponovezh, the Mashgiach, Rav Chatzkel, stood up and yelled loudly with emotion, “You can experience emuna and feel emuna with your hands! You would have to be blind not to see emuna in every step we take – you need to shut your eyes tight in order not to experience and see for yourselves that the entire world and everything in it runs according to Someone up above!” (Otzros Rabbeinu Yechezkel, p. 23)

Another talmid described how his room was situated above the lunchroom such that from his window he could see the Mashgiach walk on his daily route to the Yeshiva. The Mashgiach’s daily routine was fixed: he walked straight past this talmid’s window, never veering or even looking to his right or left, but walking straight to the Yeshiva. One day, the talmid noticed the Mashgiach stop, turn his head toward the lunchroom as if looking at something and only then did he continue on his regular routine. The puzzled talmid wondered what had caught the Mashgiach’s eye. He didn’t have long to wait before he found out.

During the mussar shmuess he heard the Mashgiach ask incredulously, “When you walk past the lunchroom and observe all the cups, bowls, plates and cutlery neatly arranged all in their places in order…does anyone think this happened all by itself? Did the plates and cups fly in the air and land perfectly arranged in order?! Obviously someone set them in order and put them away. You would have to be insane to entertain the fanciful notion that they could arrange themselves this way on their own, just as you have to be insane to believe that this world was created all by itself!” (Otzros Rabbeinu Yechezkel, p. 23)

Rav Sholom Shwadron used to tell the following story: The Mashgiach, Rav Chatzkel Levenstein, was known always to walk around with a serious expression on his face that reflected his awe and reverence – Yiras HaRomemus – that permeated his very being and all his 248 limbs and 365 sinews. Once, one of his talmidim was extremely surprised to walk in and find the Mashgiach smiling broadly – a rare sight indeed. The talmid queried the Mashgiach as to the source of his smile and Rav Chatzkel responded:

“When I used to be the Mashgiach in the Mir Yeshiva I almost never received my monthly salary on time (because of the Yeshiva’s dire financial means or lack thereof). I trusted instead in Hashem and had bitochon that He alone would see to my parnossa from other sources. When I took up the position as Mashgiach in Ponovezh I began to receive my monthly salary on time and unfortunately I lost this level of bitochon in Hashem that I had regarding my parnossa. But now – Chasdei Hashem (thank G-d) – it is some eight months that I haven’t been paid (due to the Yeshiva’s staggering debts) and I now have my bitochon back in Hashem that He will send me my parnossa in another way, and this is why I am so happy and overjoyed! (Otzros Rabbeinu Yechezkel, p. 54–55)

The Mashgiach used to relate that when his daughters were still young he would give them small change if they would think about ways to see Hashgocha Protis in their home and in their lives. And this Hashgocha was easily observed in how the Mashgiach’s household was run, as the level of poverty was great, and yet, when they would tell him what they had seen and discovered, for each story he would pay them a coin. (Otzros Rabbeinu Yechezkel, p. 73)

One of his daughters, Zlata Malka Ginsberg, related, “My father zt”l used to educate me using chinuch in the ways of Hashgocha using a variety of methods. One of his methods was to give me a notebook; he promised that if I filled in one daily occurrence of Hashgocha Protis he would buy me a prize. And true to his word, once the notebook was full, he bought me a prize, even though this cost him dearly because of our poor financial situation and his lack of means, because to my father, the need to recognize Hashgocha Protis was so important that it was worth the money.” (Mipihem, p. 196, cited in Otzros Rabbeinu Yechezkel, p.73)

The Mashgiach was once walking with one his talmidim when they passed by a drainpipe that was leaking. Upon observing this, the Mashgiach pointed it out to his talmid and remarked, “How old is this drainpipe? Probably not more than decade. And it is made of metal, and see how it is already cracked and leaking! The human body is made of soft flesh, not metal, and carries things worse than water! Our own “drains and pipes” are soft flesh and they carry such hazardous materials that are acidic and toxic like urine and waste, yet they last decades and decades, an entire lifetime; a span of seventy years or more can go by with no mishap. From my flesh I see the Divine!”

A different time, the Mashgiach asked rhetorically, “How is it that the machine we call man does not break down and need maintenance and repair as often as other machines and mechanisms do? Take a watch for example, whose mechanisms and gears are all enclosed in a metal casing shut tight. Still, every few years, it requires some maintenance to keep its timing and precision; it must be opened, dusted, cleaned and wound, and it can easily break down. Man is made not of iron, silver, or copper, but of flesh – and still sometimes he can live his whole life of some seventy years or more with nothing breaking down and no maintenance needed! (Otzros Rabbeinu Yechezkel, p.76)

In the days before the war, there were almost no private Yeshiva buildings; rather, the Yeshivos learned in local shuls and Botei Medroshim of the town or city where they were located. Once, one of the gabbo’im of the shul where the Mashgiach’s Yeshiva studied was bothering and disturbing the talmidim of the Yeshiva. He disturbed the talmidim so often that his interference became simply unbearable. He constantly interrupted their studies – and one day he kicked them out of the shul in the middle of the learning seder! With no choice left, the Yeshiva relocated itself to a different town and shul.

For years afterward, whenever the Mashgiach met anyone who hailed from that town he asked that person about the town, its shul and the welfare of the gabbai – until one day someone reported that the gabbai had died.

“And how did he die?” asked the Mashgiach.

They told Rav Chatzkel that it was on Yom Tov in the middle of Birkas Kohanim that his heart stopped and he died. In Chutz La’Aretz, Birkas Kohanim is a special occasion that takes place only on Yom Tov and the shul was in a quandary – what should they do? To interrupt the Kohanim in the middle of reciting Birkas Kohanim was impossible, yet there was a dead body in shul and the Kohanim were forbidden to become impure from tumas meis. They had no choice and decided that they had to take his body and deposit it outside the shul.

When the Mashgiach heard this, he replied, “This is the story I have been expecting to hear for some time now. I knew that something like this must happen. Just as he did, so was done to him. When he expelled the talmidim from shul, I knew that midda kenegged midda – measure for measure – Hashgocha Protis would see to it that he too would be thrown out of shul one day.” (Otzros Rabbeinu Yechezkel, page 77)

The Mashgiach Rav Chatzkel Levenstein would often repeat and review the words of the Kuzari that tefilla is like food for the soul, nourishing the soul like bread nourishes the body. Shacharis is breakfast and it should keep you satisfied until lunchtime – Mincha, he used to say. He used to give the following moshol: A hungry man once went to a store and purchased a variety of food and provisions to satiate his hunger that could last him some weeks. He stuffed the food into all his pockets, alas to no avail. The fool remained hungry and couldn’t understand why!

Of course the fool remained hungry – he filled his outer garments with food and never satisfied his true inner self by eating the food! So too do we run after fulfilling our lusts and desires for all manner of gashmiyus, yet we are never satisfied, because while the externals are stuffed, our inner being remains starving. The soul thirsts and if only the pockets of the outer garment called the body are filled, then the thirst and hunger of the inner true self – the soul – remain. But if someone were to ignore the pangs of hunger in his stomach and daven a good tefilla and learn a geshmak seder, he could feel satiated and satisfied, because this is what it means “to do without”. The body can go without and you can feel fine, whereas the soul must be satisfied or the cravings and unquenchable thirst remains. (Otzros Rabbeinu Yechezkel, Tefilla, p. 55)